Food, Farming and Filmmaking

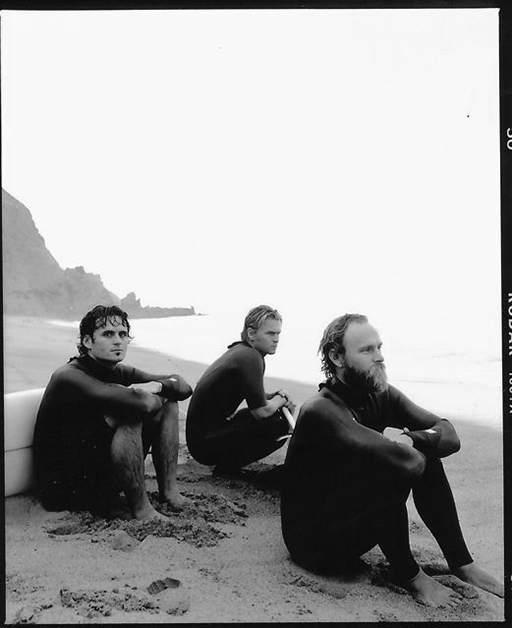

Collectively, the Malloy brothers—Chris, Keith and Dan—have traveled the world over countless times searching for great waves. Successful in the mainstream surf industry, they transitioned early on for a more holistic and purpose-driven sponsorship relationship, as Patagonia ambassadors. Also thriving movie-makers, their company Woodshed Films boasts celebrated titles, like 180° South, Come Hell or High Water, and Sliding Liberia. All their traveling may explain why we never tracked Chris down (call us!); but Keith and Dan tell us that these days, exploring locally (each live within seven miles of each other and their parents, near Ojai, CA), is where they’d rather be. We talked to the brothers about food, farming—which they grew up doing on a small scale—and filmmaking. (Photo: Jeff Lipsky)

KEITH

Where are you, right now?

In Lompoc, it’s like an hour north of Santa Barbara. [My family and I] all live pretty much in a seven-mile radius of each other, but I’m actually moving a little farther away.

So, you’re the middle child among the boys: Did you ever have the “middle child” syndrome?

I’ll tell you what I have: Dan and Chris are very talkative, and I think I’m more reserved. I don’t know if that has to do with being the middle child or not. But those guys will talk your ear off for hours on end and make conversation with almost anyone they can. I’m pretty much the opposite. I don’t know if that has to do with being the middle child or not.

Chris and Dan were born, respectively, December 21st and December 22nd, so…I think they have more similar personalities. I was born in March. I never really believed in that stuff, but if I think about it, they definitely are much more alike and they look a little more similar in ways.

What did you think about California’s Prop 37 to label foods if they are genetically modified? Did you vote on that?

I did. I definitely think that food should be labeled. I mean, that’s just simple. Why not know what you’re eating? Unfortunately, it didn’t go through, but I think it would’ve been great; it made a lot of sense. Dan and Grace were really fighting hard on that one, and I agreed with them 100 percent.

Do you think there’s anything people can do at this point to try and get something like that passed?

The fact that it nearly did is a good sign. I think that things will continue to move in that direction. In the meantime, you probably just want to buy your food at local places, where you know where it’s coming from and what it’s all about. If they would have passed 37, then it would have been touching a lot people that weren’t really concerned or aware of [the issue].

Do you think there’s something in particular that the surf community can focus on as far as surfing responsibly or lessening their impact on the environment?

Environmentalism has turned into a funny word. For me, it’s all about just doing things that are common sense, you know? Times have changed—when our grandparents were alive you could pretty much get away with doing whatever you wanted to the environment. These days, it’s changing, and everyone’s got to make sensible decisions on what they’re doing and what they’re leaving behind, and be mindful of it. I think part of the reason I’m aware of it more is because I’m in the ocean, and the ocean is one of the first things that gets tainted when it comes to emissions—or everything winds up in the ocean. How can you not think about trying to keep the planet clean when you’re actually submerged in the first thing that gets affected when there’s pollution?

If you’re a surfer, get involved in any of your local organizations that are trying to keep the water clean and be mindful of what you’re doing; make sensible decisions on what you use and where it goes.

Is there any one organization in California that you’re involved in?

Surfrider is an obvious one, but every community has their own grassroots organizations, so I would look into your own community to see what’s out there. We work with the guys from Save the Waves a lot, and they’re trying to protect breaks, so that’s a good one.

And you’re also collaborating with Patagonia, with all of the great environmental work they do. Were you ever nervous leaving the world of more commercial surf sponsorship and going with Patagonia who wasn’t necessarily proven yet in the industry?

Yeah, we were. It was definitely a risk going with a company that was not established in surfing, and working with them to help create the surf side of things. But we were also sure at that point in our careers, or lives, that we were really excited to step away from the contest surfing and the mainstream fashion. The philosophy of Patagonia just was really attractive—everything they stand for. It is the kind of company we want to work with and be a part of.

What’s your relationship with Yvon Chouinard? I imagine you got to know him well after filming 180° South?

Yeah. Yvon is great, and we’ve done some great trips together, and surfed together quite a bit in California. And Chris, Dan, and I are all good buddies with him—he’s a really fun guy to be around and he still surfs a ton. He is super active. I enjoy every time I get to hang out with him. You know, it is pretty awesome that I’ve been able to do these trips with him, and go surfing with him. He’s got a great sense of humor. I step back from it sometimes and think about who he is and I’m like, “Yeah, I’m pretty sure this guy’s gonna go down in the history books,” and that’s a pretty big deal.

Your film, 180° South, follows the 5,000-mile path Yvon Chouinard and Doug Tompkins took surfing and climbing from California to deep Patagonia. How did the film change from its original concept to when you started filming and editing?

Chris and I had a game plan to the film, but, along with other surf films, there’s a lot of room for the project to take on a mind of its own. I think that’s part of the beauty of doing a documentary-style film: you make a plan and then just see what happens and where—how the dice land, you know?

The same year we were filming the movie, the surf was huge at Mavericks, we got a great swell for that, and then we went down to Chile and a lot of snow had melted on Corcovado, so they couldn’t quite finish the climb, which was a letdown for sure; but you know, but it was one of those projects where you have to keep going. I liked that aspect of it rather than just doing a completely scripted film. It’s just a true adventure, when it’s like that.

You made Come Hell or Highwater a film about the amazing bodysurfer, and a lifeguard at Pipeline for nearly 20 years—Mark Cunningham. Why do you think his story resonates with so many people?

He’s just got a super colorful personality, super kind, and thoughtful, and funny, and nice. So that’s one end of the deal. And on the other side, he’s this incredible bodysurfer—the most renowned bodysurfer in the world, I would say. He was the awesome, nice guy in Hawaii, but he was always walking down the beach in his Speedos with his twin fins. A lot of people were like, “That’s kind of dorky,” you know? “Why would he do that?” But he just continued to do it for 30-some years. Meanwhile, everyone else has figured out how cool bodysurfing really is, how pure it is, and how hard it is to do it the way he does. So he, along with some other Hawaiians, tapped into bodysurfing 30 years before it was cool.

You rode a now infamous 60-foot wave at Mavericks. Have you ever experienced anything that epic since?

It was definitely up there in the top three biggest days of surfing I’ve ever been part of. Even though my brothers and I had been surfing and living in Hawaii, and surfed a lot of big waves, it was still really intimidating how giant that day was. Dan and I were out there together, watching out for each other. It was one of those amazing days where we spent pretty much the whole day in the water, and when we got out we were thankful we were on dry land again and made it through the day because it was a really enormous swell.

Tell me about your relationship with surfing in New York. Have you done it much?

I have surfed in New Jersey and Maine, but I don’t think I’ve ever surfed in New York. My wife is from Vermont, and so we go out and see her parents and then drag her up to Maine and surf; and I’ve gone up to Halifax and Nova Scotia. I love the Northeast and I’m looking forward to surfing it more. Even though I haven’t surfed much in New York, there’s such a great surf culture on the East Coast. The tribe of surfers out there is so enthusiastic and awesome. A lot of the kids in California are too cool for anything—too cool for a surf movie—and to see the positive energy and the enthusiasm on the East Coast is refreshing for me.

Who out of the three brothers is the better surfer?

I would say, Dan. He got into it at an early age and had a natural talent. Dan, overall, could’ve been a world champion, or something like that if he wanted to. Whereas Chris and I, you know that, we both did really well but I don’t think we were ever quite on that level. Chris never did the contests. Dan and I did the contests and we both did well, and then we kind of got disenchanted with the whole thing and stopped doing them. I did a little better professionally than Dan, but I think if he would’ve put his mind to it he could’ve done better than me.

Who do you think is the better farmer?

I think Dan is. He definitely spends the most time doing it. Realistically, though, the girls are probably better than all of us. Especially Dan and Grace. Dan’s wife, Grace, and Carla, Chris’s wife, they’re full-time. Then Chris, myself, and my wife, Lauren, work on horses with cattle. But, I mean, we all help with everything.

DAN

Where are you living these days?

I live up in Ojai, which is 50 minutes north of Santa Barbara.

And you have a whole farm “situation” out there, right?

Yeah, it’s definitely pretty small-scale at this point, because we’ve got a lot of other things going on; but my folks have a cattle ranch up here, and my brothers and our wives all live fairly close, enough to help out. My wife and my sister-in-law have something that’s between a garden and a farm. It’s a pretty good-sized plot where they grow organic vegetables, and we have a little farm stand on the weekends. It’s been a new project in the last few years, and it’s been really fun. I’ve been learning a lot.

You grew up in this kind of lifestyle, were you able to implement what you learned as a kid, today?

That kind of lifestyle—manual labor and working outside, doing exactly what my dad did—was exactly the last thing I wanted to do. As soon as I got a taste of surfing, I just wanted to do that everyday. It wasn’t until I was 25 or so, and I had been in the city and involved with the surfing industry for a while, that I started to really wake up to the fact that there’s not really a better lifestyle out there than farming and ranching and working outside. I started to take an interest in it again.

How did your upbringing shape your relationship with food today?

Well, we had horses and gardens, but we didn’t grow up on a full-on farm. It was a couple of acres in the country. So really what’s shaped how I look at food has come in the last 10 years. It’s really come through some of the people that I’ve met, and some of the literature I’ve read, and working with Patagonia, and Yvon Chouinard’s stance on food and how that affects us. About six years ago, I read an interview with [farmer and author] Wendell Berry that affected me pretty heavily—every last thing in the article stuck with me. Since then, I met my wife, who’s been farming for a while. She’s been a huge influence on my involvement with farming. She’s a way better farmer than I’ll ever be, definitely, and I’m just chipping away at figuring it out. So it’s been an evolution in the last 10 years, more than something I’ve been involved with my whole life.

Tell me about the amazing bike tour you did down the California coast this summer.

I’ve also been fascinated by the idea of getting in that traveling state of mind, but I feel like there’s so much more to learn at home that you can apply to your life, your family. So I wanted to experiment with ways to get into that frame of mind at home. I was talking to my friend Kellen Kean over a few beers, and I was like, “Hey, how fun would it be to just get on our bikes and ride down a big chunk of the California coast, and then document the whole thing, and surf as much as we could, and stay at farms and with craftspeople, and spend a month and a half on the road?” It was one of my many pipe dreams, but Kellen was really excited about it, and before long we were packing up and taking off from about a hundred miles north of San Francisco in Point Arena. There were three of us altogether: my friend Kanoa Zimmerman, a still photographer; Kellen, a videographer and still photographer; and myself. We got a ride up there and got dropped off and spent just about two months riding down the coast and working and documenting it.

What is it about traveling that’s so important to you?

I don’t know, exactly, it’s kind of a mystery to me, and it bugs me sometimes that hitting the road will awaken me so much. I wish I could feel that vibrant when I’m at home every day, but for whatever reason it just makes me feel really good to be on the road. To be honest, my goal is to access that frame of mind at home because there are just as many great adventures to be had right here, within 100 miles of my house or less. I’ll probably travel quite a bit for the rest of my life, but how to integrate that same kind of deal and be home more is actually my goal.

You’ve done a lot of trips to remote areas. Have you ever found a way to give back to the communities you experience while traveling?

I did a trip to Liberia, and I don’t know, it’s always been a bit awkward for me to show up in a really remote, poor place and feel like, “Here, we have some answers for you, and we’re gonna help you.” A lot of the trips I’ve been on have been surf trips, so we’re there doing this kind of selfish thing, and it’s always made me feel a little bit awkward to travel overseas and try to help other people. I feel much more comfortable working on things at home. I know it’s kind of strange, I’d love to just give you the answer that I’ve done a bunch of AIDS work overseas, but I’ve never felt that comfortable in that situation. I feel like there’s so much to learn in these places; but to show up with a bunch of answers has always felt awkward.

Tell me about your relationship with your brothers, do you feel like you’re a collaborator with them?

Yeah, we definitely collaborate a ton. We have since we were kids, and we have all stuck together with everything we’ve done. When it comes to surfing and the films and all that stuff, we spend a lot of time together, working on those projects. We bounce everything off of each other, so it really is a team effort. It’s worked out really well so far; not to say that we always get along perfectly, but in the grand scheme of things it works well. We’re pretty honest with each other: If we don’t like something or if it doesn’t feel quite right, we can tell each other. Working on the books and films together is an interesting process. I didn’t know if we’d be done with that stuff by this point, but we’re having a lot of fun with it, so I think we’ll continue to make stuff that hopefully we’re proud of.

So was it always this fluid, or as the youngest, did you get bullied?

I was quite a bit younger. Chris and Keith used to brawl when they were growing up—no punching in the face, that didn’t happen in our house. My brothers were both big, so I didn’t get bullied that much when I was growing up; but I definitely didn’t have too many choices, at the same time. In my family, nobody called shotgun, it was just seniority, and that’s how it’s always been. I didn’t really talk back because my brothers were way bigger. Now that we’re getting older, and all about the same size, things get questionable every once in awhile, but for the most part we all stay in line.

You left more mainstream sponsorship deals to work with Patagonia. That must have been an exciting opportunity, but were you nervous at all?

Yeah, that was interesting. A huge part of me wasn’t nervous at all because I was disillusioned with the industry and the way it worked. I just realized we were making kind of crappy clothes, and we were sort of glorified t-shirt salesmen; and if we’re going to be glorified t-shirt salesmen, we might as well sell some good t-shirts. I was bummed when the smoke started to clear and I realized that we were just a big part of a mess. From that aspect, when the Patagonia deal started to come together, I did not flinch for a second. There’s so much respect for what the brand was about. I really looked up to what they were doing for a long time, and even more so after my experience in the industry.

Then there was a side of me that was totally nervous, as far as seeing 50 other big brands—not surf brands—in other industries try to break into surfing. They never pull it off. It’s always like a bad dream: you see the clothing, you see the ads, and you’re just like, Oh my god—so that side of it was nerve-racking. But the other part of it was such a no-brainer, to be a part of Patagonia. There’s no second thought about the gear they make, and their ethos in general is exactly what we were looking for, and it’s been great.

Have you been out to New York much to surf?

I’ve surfed New York a few times, and I’ve done a couple tours with [filmmaker] Thomas Campbell when he was in New York to show his movies. I also used to pass through on my way to Europe quite a bit for competitions. Being kind of a country kid, I was fascinated by New York.

The East Coast surf scene is really interesting because some of the best surfers in the world are from there. The waves aren’t good quite as often, but when it is good you appreciate it so much. I like to be around people that are really enthusiastic about surfing. When the waves are good, all of my friends on the East Coast who are world-class surfers, surf all day long, and the guys from Hawaii and California will just go out and surf a few waves. If you’re a surfer out there, it’s like the real thing. I’ve heard people say that there’s no such thing as a real sports fan on the West Coast, it’s almost like that a little bit with surfing. Yeah, you have to really want to be a surfer. Whether the water is cold or whatever, the people that do surf have a real community there. They have something that they’re going out of their way to be a part of.

Who out of the three brothers is the better surfer?

I feel like a politician every time somebody asks me that, but we’ve all done different stuff. I mean, Chris for sure has surfed the biggest waves out of all of us—he has paddled into the biggest waves—and he’s the best at big aerials. I think that I’ve got a knack for being able to ride all sorts of different boards—we all just do different things; it just depends on what skill you’re looking at.

Who do you think is the better farmer?

Our wives. Our wives are way better farmers than any of us together. We have a hard time sitting still, so our ADD doesn’t help us too much.

Inspiring websites

- Non Gamstop Betting Sites

- Nouveaux Casino En Ligne

- Siti Non Aams Affidabili

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Online Non Aams

- Deutsche Online Casinos

- Best Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casino En Ligne

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- オンラインカジノ ランキング

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Migliore Casino Non Aams

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos En Ligne

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites UK Not On Gamstop

- Casino En Ligne Meilleur Site

- Casino Online Non Aams

- Casino Italiani Non Aams

- Casino Crypto En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne En Belgique

- Migliori Casino Online

- I Migliori Casino Non Aams

- 本人 確認 不要 カジノ

- крипто казино украина

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Casino En Ligne

- Nuovi Casino Non Aams

- Nuovi Casino Italia

- I Migliori Casino Non Aams

- Casino Fiable En Ligne