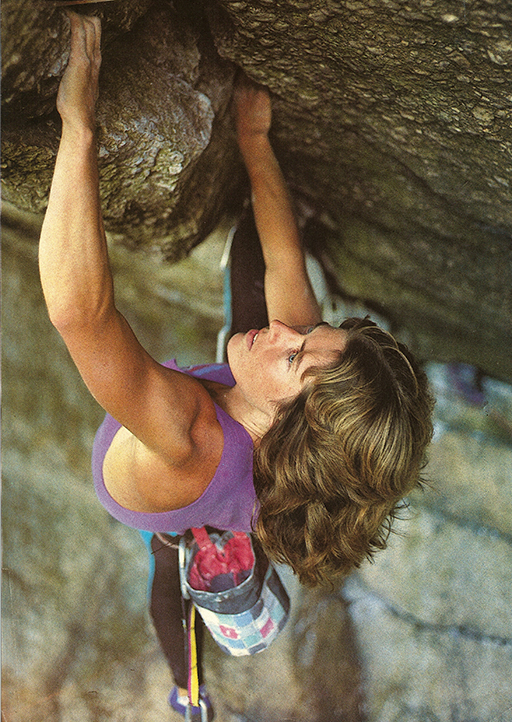

Living Legend: Patagonia’s Lynn Hill

Before the masses even knew about climbing, Detroit-born Lynn Hill was a pioneer. The Patagonia ambassador revolutionized the way people ascended mountains, and the notion of who could go up and down them, demanding equal pay and treatment for females in the field. With a background in gymnastics, her graceful style is that of a dancer, gliding up surfaces unthinkable by most men or women. She was the first to free-climb The Nose on El Capitan in under 24 hours, and at 52, she’s still inspiring us to tackle any challenge, vertical or otherwise.

Kansas City. Photo: Russ Raffa

Uphill Battles: Though things have improved significantly for women, I would say that we still struggle with the same issues. In some ways, we may have even lost ground compared to when I was a kid. Today women are expected to have a job or career and take care of the children and household duties, yet we are still paid significantly less than men. According to recent statistics, a woman only makes 70% of what a man makes in the same job. As a climber, I had to fight for equal prize money for things like the Survival of the Fittest competition. Men were getting $15,000 for prize money; we were getting $5,000. I said, “Wait a minute. This is not fair.” So we got together and told the producer and he said, “We can’t change the prize money this year but we promise to raise the prize money for the women next year.” They did increase the prize money the following year, but the women still made less than the men because we competed in fewer events.

Becoming an Ambassador. After I free climbed The Nose I ended up getting more sponsorships, which I didn’t expect. I was thrust into the limelight and it was at this point that I assumed the role of “ambassador.” I like that term a lot better than “sponsored athlete”—I think the word ambassador implies a certain responsibility to communicate the essential values related to climbing culture, as well as the preservation of the natural environment. I really enjoy my role as ambassador because I believe in helping to educate and inspire others in a positive way. It’s important to remind young kids to follow their passions and dreams rather than following the trend toward consumerism and conformism.” That’s really in essence what my image stands for: non-conventional, outside the box thinking and the importance of following our passions in life.

The East Coast: I love the directness and diversity of the East Coast. I think because the weather’s not as nice, people spend more time indoors and have developed a different way of relating to each other.

On “stuff”: Climbers of my generation seemed to be more interested in having the freedom to go rock climbing, as opposed to spending most of their time working. We preferred living on less money so that we could spend more time having fun. But the modern climber has a lot more need for “stuff” than we ever did. You see fancy SUVs, people constantly using their iPhones, and sometimes they even use a GPS to get directions to the route they want to climb. Today it’s totally different than when I first started climbing.

Trusting your instincts: When attempting a difficult climb on-sight, I try to maintain a calm and confident state of mind. I trust my sense of intuition instead of second-guessing my first instincts. If I’m feeling nervous or insecure, I’m more likely to be distracted by negative thoughts during crucial moments of difficulty. If I think to myself, “Oh, this feels hard , I might fall here!” I’m more likely to fall. The bigger the wall, the more likely something will go wrong, so I try to not to panic if something unexpected happens. I call this the mental shift, which means instead of going into panic-mode, I simply acknowledge the distraction and shift my focus to finding the best solution. Developing these mental skills requires a lot of practice.

Climbing the Nose in 23 hours: I wouldn’t say that I knew that I could do it, but I was confident that if I prepared myself properly and tried my hardest, I would find a way to realize my vision. My objective was simply to free climb the entire route from the ground to the top without a fall, in the same style as I would on a single-pitch rock climb. Though I did end up falling on the Changing Corners pitch located about 2,500 feet off the ground, I was happy to have free climbed this pitch on my third try of the day, and to succeed in making the first all-free ascent of The Nose in one day. Eleven years later, Tommy Caldwell free climbed The Nose with Beth Rodden in a four day effort, and then only two-days later, he raised the bar to a whole new level by free climbing The Nose and the Free Rider (another route on El Capitan)!

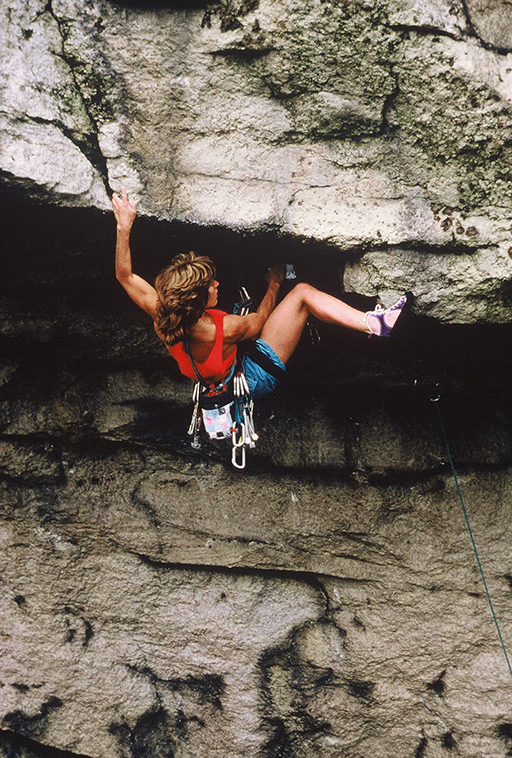

Graveyard Shift, McCarthy Wall,1983. Photo: Russ Raffa

Climbing’s rise to fame: I started climbing 38 years ago, in 1975 at the age of 14. I wasn’t old enough to drive a car so I tagged along with my older sister, her boyfriend, and my brother. In the early days, climbers used pitons for protection since there were no removable climbing devices. Even though the routes were not as difficult, they were more dangerous because they didn’t place as much protection in the rock and the hemp ropes they used were not as strong or elastic as the nylon ropes we use today. By the time I started climbing, the equipment and style of climbing had evolved. I learned to use removable protection devices such as Chouinard stoppers and hexes, which helped me develop the skills necessary for traditional style climbing. The introduction of spring-loaded camming devices didn’t happen until several years later. The Internet didn’t exist back then either and climbing wasn’t a mainstream sport at all. When I first started, I never even saw a picture of a rock climber.

The Gunks: Growing up in California, I had heard about the Gunks from a few friends and I had seen a couple of magazine articles featuring climbers such as Henry Barber, Steve Wunsch and John Bragg, who were pushing the standards of the day on the East C oast. On my first trip to the Gunks, I fell in love with the place! I was twenty-two-years-old and about halfway through my studies in college. I chose to finish my degree in Biology at the University of New Paltz, since I figured I could get a job in a health related field. I never thought it would be possible to make a living as a rock climber.

New Paltz was an ideal place to live because I could balance my time between school, climbing, and working as a rock climbing guide during the summer. I was excited to live in a completely different environment and culture. The Gunks turned out to be an important period in my evolution as a climber since the quartzite rock is quite different than the granite or sandstone formations I was used to climbing on is California.

I moved to New Paltz in 1983. During that period, the style and approach to free climbing was pretty adventurous since we were pushing new routes on difficult and poorly protected faces. We adhered to traditional style ethics, which meant that we started from the ground, without previewing the route from above. We didn’t place any bolts, and we didn’t “hangdog” (hang on the rope in order to practice the moves). A lot of times we thought we could find protection on our new routes, because we’d see a little incipient crack that looked like it might provide this. But often times we were wrong and there weren’t many opportunities to place protection in the rock. We learned to remain calm and either keep climbing up, or down climb if possible. Often times we had no choice but to keep climbing since it was more difficult to climb down. As a result, I did some of my scariest leads in the Gunks. Shortly thereafter, a new style and approach to free climbing had evolved, which is now referred to as “sport climbing.”

Women in climbing: Things have evolved a lot in a relatively short period of time. You’d think it would have gone faster since the women’s suffrage moment began over a hundred years ago! I’m 52 now, and I grew up during the 60s, which was a relatively liberal period. I never really identified with the traditional interpretation of how a woman should behave or perform. In fact, I’ve never believed in any type of discrimination based on gender, race, or other such limiting stereotypes. As a girl I liked to climb trees and I enjoyed engaging in physical activities that most people would not consider normal for a “girl.” I was called a “tomboy,” a title that I didn’t really appreciate. Though there are many strong women climbers today, climbing is still a male-dominated sport. Most people expect men to be the leaders and capable of doing harder routes than women—especially since climbing involves so much upper body strength. When I was about twenty-years-old, I made the following comment in an interview for a TV show called, Real People: “A woman may feel that she doesn’t have to perform as well as a man, but that’s not true for me. I push myself as far as I can. I don’t really think about social implications of being a ‘female rock climber.’ A woman can become very good at a sport if she dedicates herself to it.”

Collaboration vs. Individuality: Contrary to what some people might think, climbing requires a team effort. In my formative days as a climber in California, I was part of a group known as the “Stonemasters.” I found a similar group pushing the level of free climbing in the Gunks. My friends knew which routes had been done and where there were potential new routes to try. They would say, “Hey, this climb over here hasn’t been done, let’s check it out.” So we worked together as a team and established many new routes. One person would go up, and if they fell off, they would be lowered back down to the ground, leaving the rope in place for the next person. This approach, called “yo-yo” style, allowed us to work together and share in the process of establishing new routes on poorly protected faces. I wasn’t particularly looking for death-defying challenges, but sometimes it just ended up that way. And it was exciting, you know?

Outdoor vs Indoor: Climbing in a gym doesn’t offer the same satisfaction as climbing outside. The movement may be similar in some ways, but climbing outside on natural rock is much more inspiring and aesthetically pleasing. Instead of following colored sequences on plastic holds, I follow the subtle shapes and forms of the rock. Over time, I’ve learned how to interpret the forms of the rock and create an efficient flow of movement, how to place natural protection, and how to be self-reliant. Climbing has become much more popular, more accessible, and the equipment has evolved so much that many climbers take their own safety for granted. Just because a person can climb at a high lever in the gym, doesn’t mean they can climb safely outside. There have been numerous accidents due to climbers not knowing how to anticipate the potential dangers in the immediate situation. Climbing is not like ping-pong. If you make a mistake, and you don’t double-check your safety system, it could cost you your life.

I climb indoors as a means of maintaining my strength and fluidity of movement so that I can have a more enjoyable experience when I do get a chance to climb outside. Climbing gyms also provide a unique social environment for climbers, which can be a lot of fun! But I still love to climb outside most of all. It seems that with all of the demands of modern life, many people don’t take enough time to simply hang out and enjoy the peace and beauty of nature. Just being outside can be therapeutic since it allows me a chance to connect with myself, my friends, and with the natural environment.