Interview by Jim Lee

Images by Glenn Glasser

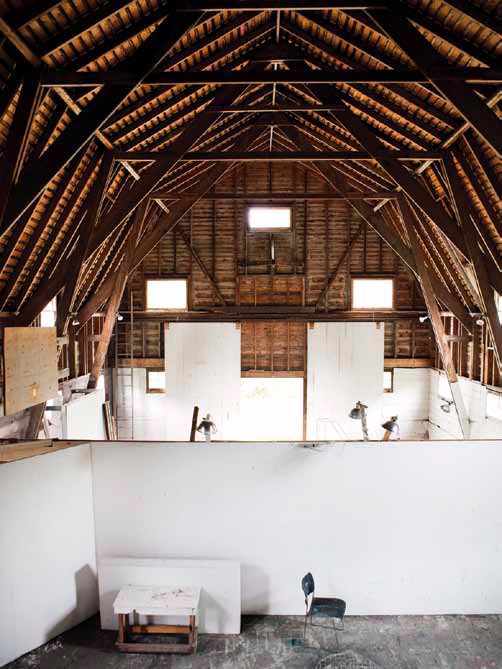

Since 1967, playwright Edward Albee, best known for the groundbreaking work, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, had run a seasonal residency for writers, painters, sculptors, and composers called The Edward F. Albee Foundation. Housed in a nineteenth-century barn, the foundation’s coupling of writers and fine artists extends Albee’s ethos that creative disciplines do better when exposed to one another. Albee talked with Brooklyn-based painter and Hofstra University instructor Jim Lee—who spent an August in 2011 working at “the barn”—about Pollack versus de Koonig, his approach to collecting, and what’s wrong with today’s art market.

You were a painter at one point, do you still paint?

No, not anymore . . . I gave that up.

I read an introduction that you wrote for a Milton Avery catalog and you mentioned that your taste in art is catholic –

– and Protestant. [laughter]

So what’s your attitude towards collecting art?

If you go to my loft in New York you’ll see a Milton Avery next to a [László] Moholy-Nagy next to an African mask — I don’t discriminate. I have a number of found objects mixed in there, which I also consider to be works of art. I don’t insist on – or my eye and my mind don’t insist on one kind of thing. I don’t have any junk around and my collection is based on an awful lot of artists that have been forgotten by a lot of people, as well as artists that haven’t made it yet. I also have my [Wassily] Kandinsky, my [Jean] Arp and my early [Marc] Chagall. I have a lot of stuff. By itself [a piece] has to be very interesting, but it also has to relate in some odd way - relate to some aesthetic historicism. I used to have a couple of Cubist paintings that I always found interesting and I hung them next to some African masks and then I saw the at the Modern Museum show [Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism]with the Picasso studio and the Braque studio with their African pieces.

What is it about the African mask?

I find them so extraordinary. The so-called primitive art is as sophisticated and aesthetically demanding as any art. And yet it was not made as art. Art shouldn’t be made as art, it should be made as something that one relates to and is useful in some kind of social way.

I find what draws me into a work of art is that it addresses more questions than answers.

That’s because questions are more interesting than answers. Answers are easier and are usually somewhat less interesting than the questions.

Are you still excited to go to the galleries?

I make my way through the trendy junk that everybody is showing these days – it’s not really serious work. It’s annoying. Art has become commerce in a way that it never was. There are so many rich people with not much taste that want to accumulate the new. And there are so many artists that are trying to catch the brass ring. You know Mark Rothko didn’t sell a painting until he was 53. So many people are trying to be fashionable and the art market is just as corrupt as any other aspect of our culture.

Do you see this as the biggest challenge for an artist today?

I find it’s tough for creative young artists because of the commerce, and for the playwrights, the novelists, the painters, the photographers, and the sculptors as well. But sculptors always have a problem because sculpture takes up too much space, and its heavy and it doesn’t fit into the decorator’s concept of what a room should look like. [laughs in jest]

Did you write a lot of criticism? And do you read any art criticism?

Yes, I’ve written a fair amount but I’d say I’m more visually oriented. Most art criticism isn’t that interesting…I get Artforum just to look at the ads

So you don’t read the New York Times or the New Yorker?

Well I like Peter Schjeldahl. Even though I find him wrong half of the time, he’s still definitely interesting, although I find his conclusions sometimes unnecessary.

Ad Reinhardt says that “In art the end is always the beginning.” How do you respond to that?

Of course it has to be.

Are we getting close to the beginning?

The end of each piece is the new beginning. Or the end of each movement is the new beginning, but more important is that everything interacts. That is most important—how all the arts interact. That’s why, as a playwright, I find painting, sculpture, and music as important if not more important to me than words and writing.

When you are writing, do you listen to music?

I don’t want to hear anyone else’s music. I don’t want to hear anyone else’s words. I don’t want anyone’s aesthetic to get in my way. I want to be focused on the reality of what I’m doing. I think, as a painter, if you were making a painting you wouldn’t even want any other paintings that you are working on in the same room as the painting you’re working on because they may influence you.

What do you listen to?

All kinds of things, but mostly classical.

Do you have a writing process?

Every time I write a play I pretend that I’ve never written one before, and I also pretend that no one else has ever written one before.

Is it a problem if you see the influences within the work of an artist?

No, not at all. I say to use them. But make them your own. We should look to those that came before us and use them. Don’t just borrow – steal. It’s not about hiding them; it’s about how you incorporate it into your own aesthetic.

Select one: Pollock or de Kooning.

Hmm . . . I don’t’ know. They’re both interesting. I tend to like de Kooning’s early black and white work but I think the last work is just terrible.

You just hurt me on that one.

You know, Pollock did some extraordinary work and is also important. It’s difficult to pick one over the other. You need to see what happens to an artist.

Is it difficult because Pollock died so early?

It’s tough to say what would have happened. You take an artist like Motherwell - he was interesting in the ‘50s and even some of his big black and white “Kliney” paintings are interesting but after that . . . And look what happened to Kline when he added color to his work – it fell apart completely. We can’t judge what Pollock would have done, we really can’t. I don’t know what would have happened. I mean what if he’d stopped drinking? It might have fallen apart.

Is there anything for artists to react to these days?

The problem is the spectrum of what to take from has gotten so huge and the varieties of middlebrow experience that can be imitated are so tempting. I just wish that art would stop being popular for about thirty years. I think it would settle itself out and that would leave the good people to go forward because they’d be painting just because of painting. What I do find is that sculpture is getting more interesting – quite often more interesting than painting. For example I find Cy Twombly’s sculpture more interesting than his paintings, ultimately.

Who would you give a lifetime achievement award to?

I give it to [the poet and playwright] Sam Beckett, although I don’t like some of the painters he liked.

Who did he like?

Some good second-rate French painters that I didn’t think much of, but he did like good music. He listened to good music. So did Rothko, he listened to good music when he painted.

You were close with Rothko?

Yes, we knew each other pretty well.

From our conversation, I take it that you need a lot of crossover in life in terms of creativity.

I think crossover is essential to creativity. It is one of the reasons the foundation works as well as it does. If there were nothing but poets here, who’d learn anything? The artists are supposed to interact. Having different disciplines here makes it pretty useful.

What do writers need?

Isolation and a small space and a beach to go to and look at things.