Creative multi-tasker Jauretsi Saizarbitoria is on a mission to warm the icy, generational stalemate between the US and Cuba. Born in Miami to émigrés who ran one of Cuba’s most popular restaurants, Saizarbitoria does this by fostering positive dialogue on her blog, radio show, and in her directorial debut east of Havana. For our collaborative publication with the Miami Beach Edition, we spoke with Jauretsi below.

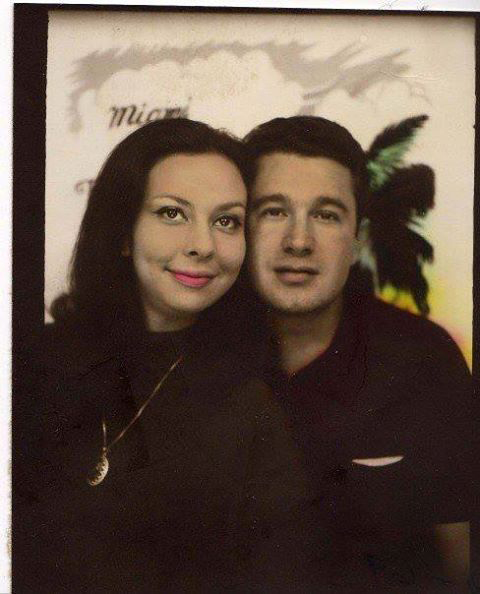

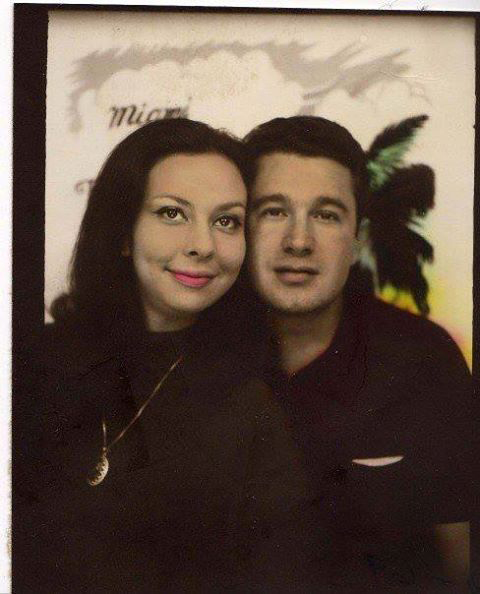

Jauretsi’s parents met when Totty happened upon Juanito, the successful new Centro Vasco restauranteur, shortly after the business moved to Miami from post-revolution Havana.

Jauretsi’s parents met when Totty happened upon Juanito, the successful new Centro Vasco restauranteur, shortly after the business moved to Miami from post-revolution Havana.

Jauretsi’s mom Totty arrived in Miami at age 16. She quickly became a respected hairdresser, working with clients like Nancy Sinatra and Zsa Zsa Gabor during the Fountainbleau Hotel’s infamous Rat Pack era.

Jauretsi’s mom Totty arrived in Miami at age 16. She quickly became a respected hairdresser, working with clients like Nancy Sinatra and Zsa Zsa Gabor during the Fountainbleau Hotel’s infamous Rat Pack era.

Juanito, patriarch of the Saizarbitoria clan, sits centered among original Centro Vasco patrons. This mainstay for Basques, Spaniards, and athletes was famous in the 1940s and 50s in Havana.

Juanito, patriarch of the Saizarbitoria clan, sits centered among original Centro Vasco patrons. This mainstay for Basques, Spaniards, and athletes was famous in the 1940s and 50s in Havana.

How are you involved with the Miami Beach Edition?

I was invited to do a playlist for the [hotel]. I was a DJ for 20 years, and have a lot of music. Being a Cuban-American, I collect a lot of Latin funk and Cuban classics. I like to keep it funky sometimes.

What’s happening in the contemporary Cuban music scene?

That was one of the questions I had when I went down to do my documentary [East of Havana]. On a global level we’re all very familiar with the Buena Vista Social Club type voice, which is so much a part of what Cuba is. But for me as a young Cuban-American, I wanted to know what the teenagers were talking about.

So I went down there to figure out what the “word on the street” was, and search out street parties to find out what young Cubans were expressing internally. Ultimately, they are the ones who will decide what’s going to happen in Cuba. This was the early 2000s, which are considered the “golden years” of rap down there. Hip hop began in New York in the 70s, but just like anything, Cubans caught onto it 20 years later. But the scene was blowing up and a fever was brewing.

American hip hop has gangster rap, but there’s not as much of that culture in Cuba, and really no money down there—no bling rap going on. So when they play it, it’s more of a critical view on society—their form of social activism. They’re doing it because it’s therapeutic and it’s a way to discuss the neighborhood: the 90s were a very tough decade for young Cubans, with food shortages, blackouts, and a desperate lack of basic needs.

What’s happening now is that the hip hop scene has mutated and morphed because the government put rules and regulations on it. Here’s the inherent conundrum of rap in Cuba: it’s an art rooted in freedom of expression, obviously improvising and freestyling, and you’re in a country where there’s no freedom of expression politically. So at one point those factors collided.

When you went down to film East of Havana was that your first time in Cuba?

I had been there a few times before we filmed. If you’re a Cuban-American and you go back to Cuba, it’s traditionally perceived as being a traitor to your people. So you have to get past all that guilt while breaking through. For my parents’ generation, it’s almost like the boogeyman on the other side of the wall. Their last memories were traumatizing on the island. The first trip is not the trip that you’re like, “I get it.” You have to go around the island and have a lot of conversations. It’s a really interesting healing process of our generation that I think a lot of young Cubans need to go through. I’ll say to young Cubans, “Have you been back?” and they’ll say, “No, I’m waiting for Fidel to die.” My advice to them is “You need to start. It’s going to be a long road.” I think my generation is responsible for holding hands and reconciling. There’s a mess down there in some ways and a lot of work that needs to be done. I don’t think that’s going to happen until the young Cuban-Americans go down there and roll their sleeves up and ask “How can we help?”

Is it mostly Cuban-Americans who are the ones to affect change? Will the US or Cuban governments have anything to do with it?

The government runs everything in Cuba; there are no independent businesses. So when you engage with business in Cuba, you’re really doing business with the government, which is one of the reasons the older Cubans get pissed off about people visiting Cuba. Their rhetoric is, you’re funding tourism, which is keeping the country afloat, and pretty much supporting the enemy—which is a really hardcore way of looking at it.

But my point is when you go down there, and you have to stay at a hotel sometimes, there are other things you can do to empower the community. Maybe I have an issue of The Economist in my backpack from Miami and I give it to someone who can’t buy The Economist in Cuba. Perhaps I can offer an old cell phone to a local friend? I call it cultural exchange and I think it’s 50/50. As much as an American can go down there with material goods, in return, they have taught me so much more than I could have ever learned about the culture. It’s more of a form of equal exchange—spiritually and in every other way.

What was it like for your family to leave Cuba and make an entirely new home in Miami?

It’s a post-traumatic situation. In the 60s, several of my parents’ generation were fleeing to Miami for just a couple months, planning to go back. No one thought they would stay 50 years. So the running dialogue was, “It’ll only be a year…it’ll only be two years…it’ll only be 10 years,” like they were going to be there temporarily. No one knew it was going to be a lifetime.

In the 70s when they realized they were staying, there was a whole round of elder Miami Cubans who tried to take back Cuba on a paramilitary level. In the 80s the hardliners learned how to put a suit on and go to Washington DC and really implement deeper laws with the embargo. The fight became less cowboys and Indians and more governmental. Instead of militaristically taking it back, they were going to create laws to choke Cuba until they fell to their knees and asked for democracy.

The issue with the embargo is, it’s been 50-something years and it hasn’t worked yet. So the voice that I play with and write about on my blog, and put on the radio show—the philosophy—is less about isolating Cuba and more about engaging with Cuba again.

In general, what was it like growing up in Miami for you?

It was awesome. Southern Florida does not feel like the United States at some points. When you come to Miami, you communicate mostly in Spanish. Your grandparents never learn English. The way the neighborhoods are set up, everyone at the bank, the supermarket, the pharmacy, speaks Spanish. You’re raised hearing Celia Cruz play out of the radio in the kitchen, having cafe con leche in the kitchen. Not to mention at the dinner table everyone’s arguing about Fidel Castro, and older Cubans are waxing poetic. The running joke in Miami is that everything was better in Cuba. It’s like, “This breeze was better in Havana.”

Part of the paradox of being raised in Miami is you have Cuban culture shoved down your throat, but then the second you say, “I want to go there!” you get slapped in the face. You can love it to death—this idea of Cuba—but don’t ever even think twice about going 90 miles south.

Though eventually you made the pilgrimage back to Cuba?

My family had a really hot restaurant [Centro Vasco] in Cuba in the 50s. In the 60s my dad brought it to Miami. Everyone went across the pond and just landed in Dad’s place. Celia Cruz played there, all the greats played there. Fast forward to the mid 90s: we booked one woman who still lived in Cuba to play there, and that started a lot of protests in Miami, and much darker stuff that I won’t even share—threatening phone calls and stuff.

My parents did not cancel the show, despite the pressure. If anything it turned into many nights sold out. One night turned into eight sold-out shows, and in the middle of the night, someone threw a Molotov cocktail and torched the restaurant. Eventually, reservations fell out of the book, people freaked out, kids’ birthdays moved. This 1950s McCarthyism-type fear of Communism is very much alive in Miami, although things are changing slowly. We lost a 50-year family business because of one show, and the fact that some cannot separate art and politics.

As deep of a curse as it was to my family, it liberated me to go to Cuba, because when that happened, I looked at my parents and I said “I’m going.” We lost our house, we lost the building, and I was like, “That’s it,” there’s nothing else left to lose at this point. I went there to explore the roots of my culture, and was awoken to a whole new movement percolating.

You’re a multi-tasker in terms of creativity from curation, film, writing, digital content. Did being raised around the restaurant and the community you grew up in in Miami help you with all these varied roles?

Only in my later years have I learned this about myself, but I’ve come from a place of following my nose for my whole life and following my passion. With that comes jumping careers, moving to New York by myself without knowing anybody, and starting from scratch after being established in Miami growing up. I think having Cuban DNA and knowing people who persevered hardships affected me. Many successful Cubans who were exiled lost everything and had to come to a brand-new country, learn a brand-new language, and start from scratch. A lot of my elders became successful all over again, from sweeping floors to being CEOs again. So it wasn’t until recently that I thought, “Wow I guess I’m not really afraid of these peaks and valleys in a traditional sense.”

I guess the answer is that the highs and lows don’t really scare me, it’s just following your gut. If you really set your mind to it, success is in your hands. I learned that from the people I grew up with. On top of the fact that I learned the gift of gab, and all the other fun Cuban stuff that lights up a room [laughs].

A Family Affair

Jauretsi talks shop with her parents Totty and Juanito

Jauretsi: Centro Vasco was one of the most popular restaurants in Cuba. What was it like for Juan [Jauretsi’s grandfather] to move on and take it to the next country?

Totty & Juanito: After 20 years of working in Cuba and the Cuban government taking our business away and everything we worked for, starting again wasn’t easy. We had to rent a small restaurant in Miami that opened on May 20, 1962. Then, after three years of it going very well, we bought another space and located it to a new building. It was called The Garden on 8th Street (Calle Ocho), the heart of Little Havana. This space was to become the classic Centro Vasco in Miami.

What was the cultural and political atmosphere like in Miami back then?

Juan: Cubans arrived fleeing Fidel Castro and the revolution, and the atmosphere was very difficult and sad. They took everything—their houses and their businesses. The government [confiscated] all homes and restaurants. We had to leave because of not sympathizing with [Castro’s] revolution.

How did you and other Cuban exiles make Miami feel like a new home?

Juan: At first it was very difficult to adapt. We worked seven days a week for several years and then we started to get accustomed. It began to feel like home.

How has Miami changed in the decades since you’ve been living here?

Juan: In the 60s Miami was very small, with a lot of older people. Nobody went out at night and the TV was on until 11 pm. When we opened the first restaurant, Americans would come to try Spanish food. At the time they still wouldn’t drink wine, they weren’t used to wine. They would order paella and then the waiter would ask, “Want to order a drink?” and they would get coffee. It would taste horrible, a paella with an American coffee!

Why wouldn’t they drink wine?

Totty: At the time wine wasn’t in. Wine started to introduce itself little by little because of the Spanish and the Latins. You know, Juanito has eaten with a glass of wine his whole life, and you know, Cubans generally drink beer. But imagine sitting down with an American coffee! It’s just funny because these are the things that were done at the time. Wow, but so gross.

What was the concept behind Centro Vasco restaurant when it first opened in Miami?

Juan: The concept was to maintain the tradition in the food and to attract the same kind of clientele we had in Cuba, all the people that were arriving [in Miami] at the time.

What kind of people frequented Centro Vasco when it was operating in Cuba, and then when it was open in Miami?

Totty: In Cuba there were first the Spanish. After a while he became famous with a restaurant in the Vedado area in 1952. Famous people started to become the clientele—families, VIPs, and artists. Among them Ava Gardner, Errol Flynn, Marlon Brando, Hemingway…until the end of the 60s. At the restaurant in Miami, the most important associations of Cubans would gather all the time. A lot of US Presidents came to visit—Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan. A lot of VIPs—Madonna, Jennifer Lopez. Gianni Versace was a regular visitor. Aside from that, it was traditional Cuban families from all over the country, and foreigners who wanted authentic Spanish cuisine and a Cuban experience.

Cover: Jauretsi portrait. Photo: Gerald Forster.

Jauretsi’s parents met when Totty happened upon Juanito, the successful new Centro Vasco restauranteur, shortly after the business moved to Miami from post-revolution Havana.

Jauretsi’s parents met when Totty happened upon Juanito, the successful new Centro Vasco restauranteur, shortly after the business moved to Miami from post-revolution Havana. Jauretsi’s mom Totty arrived in Miami at age 16. She quickly became a respected hairdresser, working with clients like Nancy Sinatra and Zsa Zsa Gabor during the Fountainbleau Hotel’s infamous Rat Pack era.

Jauretsi’s mom Totty arrived in Miami at age 16. She quickly became a respected hairdresser, working with clients like Nancy Sinatra and Zsa Zsa Gabor during the Fountainbleau Hotel’s infamous Rat Pack era. Juanito, patriarch of the Saizarbitoria clan, sits centered among original Centro Vasco patrons. This mainstay for Basques, Spaniards, and athletes was famous in the 1940s and 50s in Havana.

Juanito, patriarch of the Saizarbitoria clan, sits centered among original Centro Vasco patrons. This mainstay for Basques, Spaniards, and athletes was famous in the 1940s and 50s in Havana.